Deprenyl and Alzheimer’s Disease – Update

Deprenyl and Alzheimer’s disease—update

By Ward Dean, M.D.

Deprenyl (aka seligiline, trade names Eldepryl®, Jumex®) was discovered in Hungary in the 1950s and was patented by Professor Jozsef Knoll of Semmelweis University in Hungary in 1962. Deprenyl was shown to extend maximum lifespan in animals, enhance cognition in normal healthy animals, reduce the symptoms and delay the progress of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease and act as an aphrodisiac and performance-enhancer in male animals and men.

In our book, Smart Drugs II, the Next Generation (1993), based on a number of positive studies, we wrote that deprenyl appeared to be a powerful weapon against Alzheimer’s disease.1 At about that same time, Professor Knoll recommendedthat; “Alzheimer’sdisease patients need to be treated daily with 10 mg deprenyl from diagnosis until death.” 2 Curiously, research on selegiline peaked ten years after the publication of our book and plummeted thereafter. What happened, I wondered, to the interest in what I still believe to be an effective antiaging, cognitive-enhancing substance?

Cochrane Review Meta-Analyses Slams Deprenyl’s Value as Alzheimer’s Drug

From 2000-2003, a series of articles critically reviewed deprenyl’s efficacy in Alzheimer’s disease—two in Cochrane Reviews,3,4 and one in International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.5 Cochrane Reviews is considered the “gold Standard” for “meta analyses,” in which the authors critically analyze a number of double-blind controlled studies to arrive at a consensus of “evidence-based medicine.” All three of these meta-analyses relied on the same statistician, reviewed essentially the same studies and arrived at progressively more negative conclusions in each review.

The first Cochrane Review conceded that of the 17 trials considered, 14 trials reported beneficial effects of deprenyl in the treatment of cognitive deficits, and 3 reported improvements in behavior and mood. Pooled data for all cognitive tests suggested significant benefits with deprenyl compared to controls. Two years later, a follow-up report by the same statistician (Birks)–but with different co-authors—again reported that overall, the studies indicated that deprenyl -users demonstrated improved cognition at 4-6 and 8-17 weeks. But the following year in 2003, the authors of the first Cochrane Review issued a blisteringly negative third meta-analysis.5

In this third review, the authors again positively reported that; “the meta-analysis revealed benefits on memory function shown by improvement from several cognitive tests,”6-18 and “The combined memory tests, and overall combined cognitive tests…showed an improvement due to deprenylcompared with placebo at 4-6 weeks and 8-17 weeks.” [Emphasis added] In addition, in “several studies [which] assessed activities of daily living using several different scales,6,9,11,12,14,15 “the combined tests showed an improvement due to deprenyl at 4-6 weeks.”5

Inexplicably, the reviewers then concluded paradoxically and without apparent justification that “Despite its initial promise, i.e. the potential neuroprotective properties, and its role in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, deprenyl for Alzheimer’s disease has proved disappointing. There would seem to be no justification, therefore, to use it in the treatment of people with Alzheimer’s disease, nor for any further studies of its efficacy in Alzheimer’s disease.”5

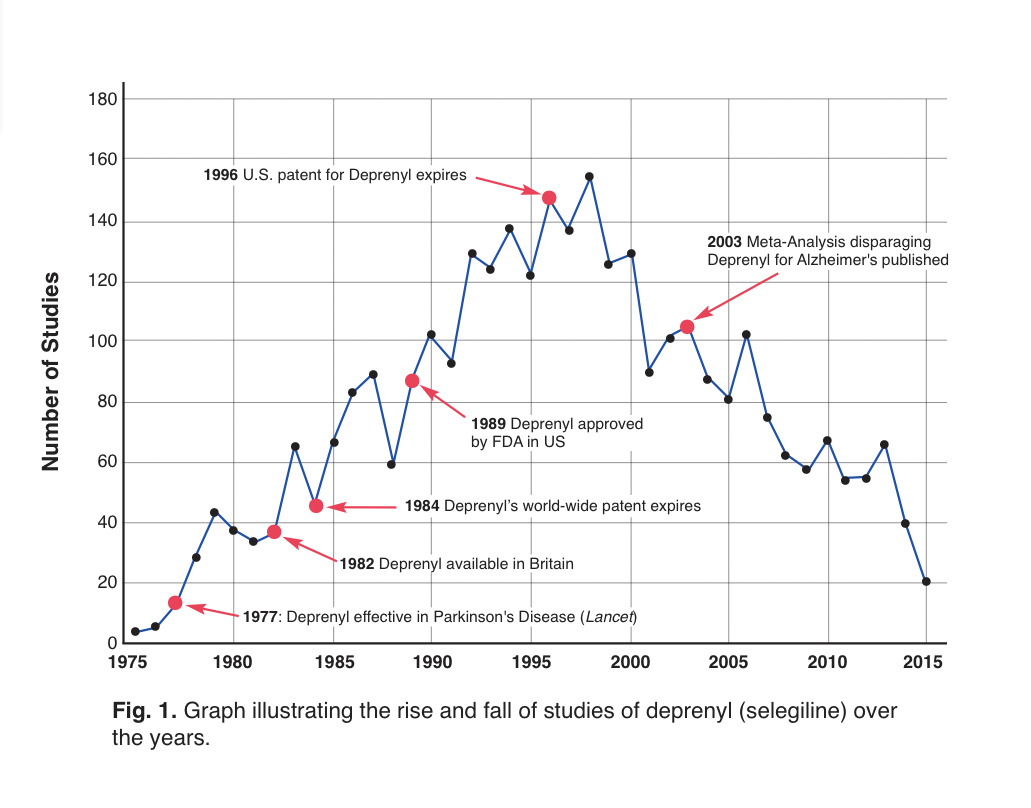

With that disparaging conclusion, further research into the use of deprenyl for Alzheimer’s use ground to a screeching halt (Fig. 1). Another understandable reason for the fall-off in published studies about deprenyl is that brand-name protection for Eldepryl® (selegiline) in the U.S. had ended, and there was little likelihood for pharmaceutical-sponsorship of further trials.

Figure 1: Time-line of selegiline studies.19 Note the dramatic drop in annual studies following the publication of the disparaging meta-analyses.

Analysis of the Meta-Analyses–Review of the Reviewers

I was thunder-struck by the negative conclusions reached by the Cochrane Reviewers, which seemed to fly in the face of the positive clinical studies that we had reviewed in SDII—and, for that matter, which were included in the Cochrane Reviews. Admittedly, Alzheimer’s disease is a chronic debilitating disease, that results in progressive death of brain cells, for which there is no known definitive cure. Deprenyl is not the “silver bullet” for Alzheimer’s disease that we all hope for—but it has been shown to delay neurodegeneration, and restore the catecholamine balance in brains altered by Alzheimer’s disease. Certainly, any treatment that slows or reverses this debilitating disease to any degree, with minimal or no adverse side effects, is a welcome addition to our therapeutic armamentarium.

I re-examined the 17 studies in the meta-analysis, as well as the studies which were specifically not included–as well as a major study that had not previously been considered (but which should have been)—to determine the credibility of the meta-analyses.

Of the papers included in the reviews, most reported positive results to varying degrees. Unless otherwise noted, the studies were all double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with Alzheimer’s patients, using 5 mg deprenyl twice daily. Here, in summary, are the outcomes of the positive studies I could find (several were obscure and unavailable):

- Twenty patients diagnosed between stages 3 and 5 of primary degenerative dementia were treated for 90 days with deprenyl or placebo. Subjects in the deprenyl group demonstrated improvement in both attention and memory measures.6

- Ten patients were given either a placebo or deprenyl for two months, resulting in improvedmemory, attention, and language abilities among those who received the drug, while those on placebo showed worsened cognitive efficiency and reduction of parietal lobe cerebral blood flow.7

- One hundred seventy-three nursing-home residents with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease were treated with deprenyl or placebo for 24 weeks, resulting in improved cognitive and behavioral functions.9

- In a 14-week study of deprenyl or placebo in twenty-five outpatients, there was a significant benefit of deprenyl treatment on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), the Dementia Mood Assessment Scale (DMAS), and in cognitive function on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive (ADAS-COG) with deprenyl compared to placebo. The authors concluded that “short-term selegiline treatment produced an improvement in behavior and cognition.”10

- In one hundred nineteen patients treated with deprenyl or placebo for 3 months, deprenyl significantly improved the activities of daily living, dementia symptoms and many cognitive functions including memory, attention and visuospatial ability, and was reported to be … “a useful and reliable tool … to improve cognitive functions and reduce behavioral alterations, without frequent or severe side effects.” 12

- Six months’ treatment of deprenyl vs placebo in 20 patients showed significant positive effects of deprenyl on memory and attention.13

- Of 341 patients treated with deprenyl (10 mg a day), alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E, 2000 IU/day), both deprenyl and alpha-tocopherol, or placebo for two years, “treatment with selegiline or Vitamin E slows the progression of Alzheimer’s disease.”14

- Sixty-seven patients were given deprenyl or placebo, and were evaluated every six months with the mini–mental state examination (MMSE). The deprenyl group deteriorated significantly less than the placebo group.18

- Nineteen patients were treated with deprenyl or placebo for six months. The deprenyl -treated patients showed significantly better performances in learning, long-term memory skills, cognitive functions and behavior. The researchers concluded that; “Deprenyl represents an effective treatment for memory disorders in Alzheimer’s disease.”20

- Deprenyl (10 mg/day) or placebo given to 12 patients resulted in clear positive trends in favor of selegiline on several dementia rating scales.21

Thus, at least 10 of the 17 studies showed apparent benefit from deprenyl in Alzheimer’s patients. Although 5 studies did not find any benefit from deprenyl, there were no adverse effects.

Deprenyl Studies excluded from the Meta-Analysis

The Cochrane Review authors also considered but excluded an additional 16 studies, for various reasons. Of these studies which reported positive results:

- Seventeen Alzheimer’s patients received deprenyl in doses of 10 mg or 40 mg per day. Total Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) scores improved significantly on the 10 mg dose, and measures of anxiety/depression, tension, and excitement decreased. Approximately half of the patients’ conditions improved clinically, with increased activity and social interaction, along with reduced tension and retardation. The behavioral changes were associated with improvement in performance on a complex cognitive task requiring sustained effort. Unexpectedly, these improvements were not seen with 40 mg.22 Similarly, improvement occurred in episodic memory and complex learning tasks requiring information processing and sustained conscious effort with deprenyl 10 mg/day, but not with 40 mg.23

- Eleven elderly female patients—7 with Alzheimer’s and 4 with multi-infarct dementia — were treated with deprenyl. Improvement was most notable in the Alzheimer’s patients–especially regarding self-care, short term memory, and mental alertness.24

- Twenty-eight patients treated for three-months with deprenyl or placebo resulted in a global improvement of cognitive performances in the deprenyl group compared to placebo.25

- Five patients with behavior problems, ranging in age from 50 to 82, were treated with deprenyl for 8 weeks. The authors reported; “Clinical significance was noted by improvement in cognition,” and “Alzheimer’s patients with behavior problems may benefit from selegiline therapy.”26

- A 4-week study of fourteen patients treated with deprenyl demonstrated significant improvements on the agitation and depression factors of the BPRS, the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia, and spouses’ blind rating (SBR). Recall improved on the Buschke Selective Reminding Task. Overall, the authors concluded that; “selegiline may be associated with improvement in behavioral and cognitive performance.”27

- Twenty-two patients (14 men, 8 women) mean age 62.8, in a double-blind cross-over study for 26 weeks, showed that deprenyl possesses significant beneficial activity on memory parameters, with an improvement both in information processing abilities and in learning strategies.28

Comparisons and Combination Therapy–Deprenyl vs (or combined with) other Cognitive Enhancers

- Oxiracetam, (anootropic drug similar to piracetam)was tested againstdeprenylinatrialinvolving22menand18 women. Deprenyl was given to one group and 800 mg oxiracetam per day was given to the other group. Deprenyl was more effective than oxiracetam in improving higher cognitive functions and reducing impairment in daily living. Deprenyl helped more with short and long-term memory, sustained concentration, attention, verbalfluency,andvisuospatialabilities.28

- In another 3-month study, deprenyl was compared to phosphatidylserine (100 mg twice daily) in forty patients (24 men and 16 women). For most measures of cognition, “the selegiline group showed improvements superior to those obtained in the phosphatidylserine group.”29

- Deprenyl was also compared to acetyl-L-carnitine (ALC) (500mg twicedaily) in forty patients (13 men, 27 women, 56 to 80 years). ALC and deprenyl both led to global improvements in the capacity to process, store and retrieve given information, as well as improvements in verbal fluency and visuospatial abilities. However, the degree of improvement was even more effective with deprenyl than ALC.30

- Deprenyl added to the regimen of 10 patients receiving either Tacrine® or physostigmine was assessed in a 4-week pilot study. Deprenyl was associated with significant improvement in scores on the cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS), suggesting additive effects of deprenyl to the effects of cholinesterase inhibitors.31

Largest, Most Positive Study Ignored by Meta-Analyzers

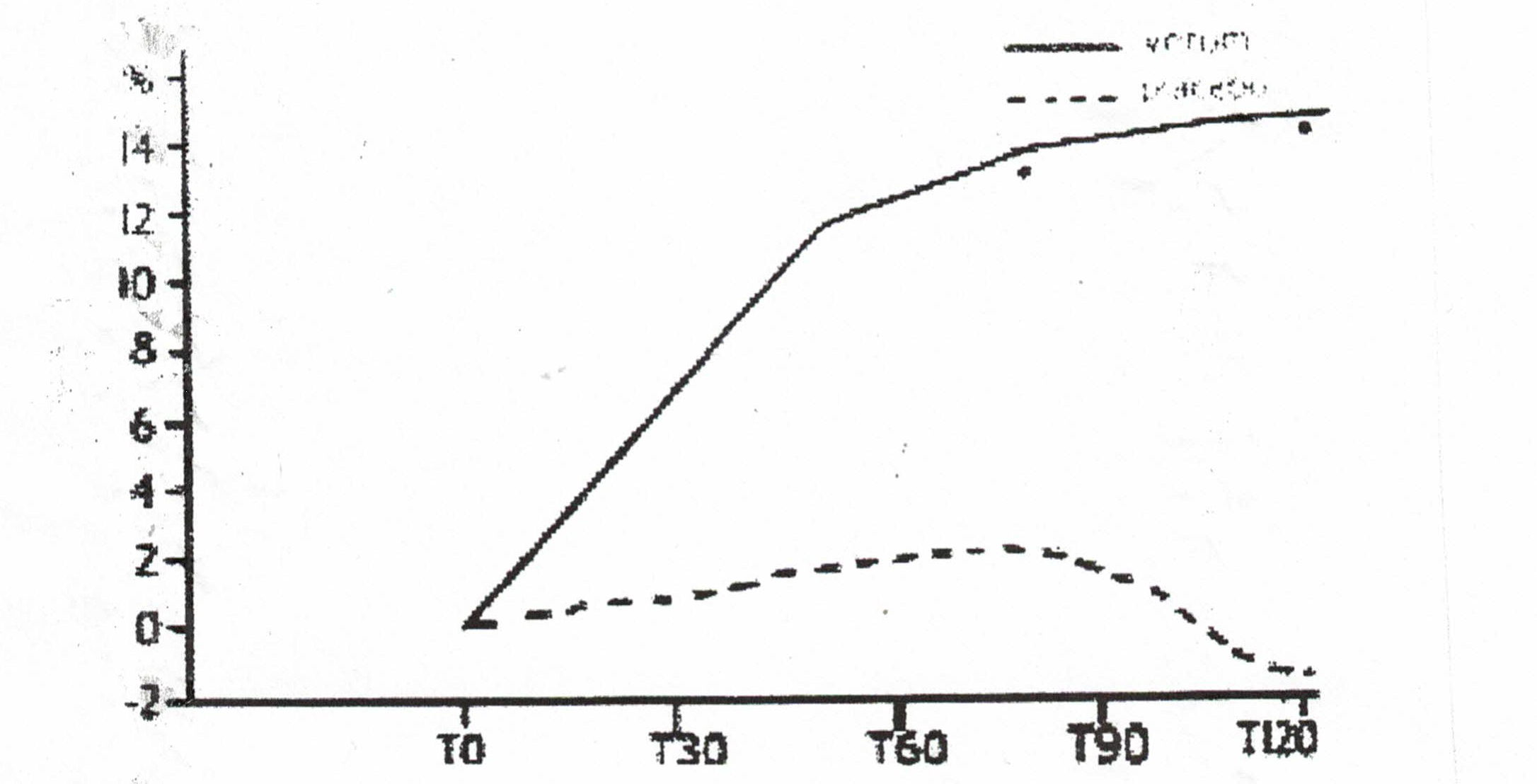

- One large study that was not evaluated by the Cochrane Reviewers was conducted by scientists from the University of Catania in Italy. Two hundred outpatients over 65 were treated with deprenyl or placebo for 120 days. The physicians conducting the test and the patients themselves agreed that deprenyl treatment was beneficial. The17-item scale of clinical assessment for geriatrics (SCAG) was used to determine efficacy. One element of the SCAG was the Short Term Memory scale, which indicated dramatic improvement in the deprenyl users (Fig. 2). When deprenyl treatment was suspended, the improved cognitive functions began to deteriorate.32

Figure 2: Improvement in SCAG short term memory scale with deprenyl (solid line) compared to placebo (broken line).32

Conclusion

Unfortunately, Alzheimer’s Disease is presently an incurable neurodegenerative disease. Although a number of treatments are used to minimize or improve the symptoms, there is no proven treatment to reverse its downward course. By the time the diagnosis is made, the patients are usually past complete recovery, since the neuropathological changes in the affected neurons are on an irreversible downward path.

Since Alzheimer’s disease is believed to be a byproduct of “normal” brain aging, our best hope to significantly decrease its prevalence is to slow the natural aging of the threatened neurons by administering a protective substance like deprenyl. Although deprenyl does not alter the landmark pathological changes of Alzheimer’s once they have become manifest (such as neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid beta or abnormal tau proteins), it has demonstrated over and over via multiple mechanisms that it can slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, and in many cases enhance cognitive and behavioral indices of the disease. Therefore, the optimum time to use selegiline is before the disease presents.

References:

- Dean W, Morgenthaler J, Fowkes SW. Smart Drugs II, the Next Generation. Smart Publications, Petaluma 1993.

- KnollJ.(-)Selegiline-medication:Astrategytomodulatetheage-relateddeclineofthe sriataldopaminergicsystem.JAmGeriatrSoc40(8):839-47,August1992.

- Birks J, Flicker L. Selegiline for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000442.

- Wilcock GK, Birks J, Whitehead A, Evans SJ. The effect of selegiline in the treatment of people with Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of published trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002 Feb;17(2):175-83.

- Birks J, Flicker L. Selegiline for Alzheimer’s disease.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(1):CD000442.

- Agnoli, A, Martucci, N, Fabbrini, G, et al., Monoamine oxidase and dementia: Treatment with an inhibitor of MAO-B activity, Dementia. 1990, 1:109-114.

- Agnoli A, Fabbrini G, Fioravanti M, Martucci N. CBF and cognitive evaluation of Alzheimer type patients before and after IMAO-B treatment: a pilot study.Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1992 Mar;2(1):31-5.

- Sunderland T, Molchan S, Lawlor B, Martinez R, Mellow A, Martinson H, Putnam K, Lalonde F. A strategy of “combination chemotherapy” in Alzheimer’s disease: rationale and preliminary results with physostigmine plus selegiline.Int Psychogeriatr. 1992;4 Suppl 2:291-309.

- Filip V, Kolibás E. Selegiline in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a long-term randomized placebo-controlled trial. Czech and Slovak Senile Dementia of Alzheimer Type Study Group.J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1999 May;24(3):234-43.

- Lawlor BA, Aisen PS, Green C, Fine E, Schmeïdler J. Selegiline in the treatment of behavioral disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease.Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997 Mar;12(3):319-22.

- Loeb C, Albano C. Selegiline – A new approach to DAT treatment. Proceedings of the European Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Extrapyramidal Disorders; 1990 Jul 10-14, Rome. 1990. http://www.psych.org/clin_res/pg_dementia_8.html.

- Mangoni A, Grassi MP, Frattola L, Piolti R, Bassi S, Motta A,·Marcone A andSmime

- S. Effects of a MAO-B inhibitor in the treatment of Alzheimer ‘s disease. Eur Neurol (Switzerland) 31(2): 100-7,1991.

- Piccinin GL, Finali G and Piccirilli M. Neuropsychological effects of L-selegiline in Alzheimer’stypedementia.C/inNeuropharmacol13(2):147-63,April1990.

- Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, Klauber MR, Schafer K, Grundman M, Woodbury P, Growdon J, Cotman CW, Pfeiffer E, Schneider LS, Thal LJ. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study.N Engl J Med. 1997 Apr 24;336(17):1216-22.

- Tariot PN, Goldstein B, Podgorski CA, Cox C, Frambes N. Short-term administration of selegiline for mild-to-moderate dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1998 Spring;6(2):145-54.

- Freedman M, Rewilak D, Xerri T, Cohen S, Gordon AS, Shandling M, Logan AG. Selegiline in Alzheimer’s disease: cognitive and behavioral effects.Neurology. 1998 Mar;50(3):660-8.

- Burke WJ, Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP, Bayer BL, Ranno AE, Willcockson NK. Selegiline in the treatment of mild dementia of the Alzheimer type: results of a 15-month trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993 Nov;41(11):1219-25.

- Riekkinen, PJ, Koivisto, K, Helkala, EL, et al. (1994), Long-term, double-blind trial of selegiline in Alzheimer’s disease, Neurobiology of Aging, 15 (Suppl 1): S67.

- Figure adapted from data obtained at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=selegiline

- Finali G, Piccirilli M, Oliani C and Piccinin GL. L-selegiline therapy improves verbal memory in amnesic Alzheimer patients. Clin Neuropharmacol (USA) 14(6): 523-36,1991.

- Heinonen EH, Savijärvi M, Kotila M, Hajba A, Scheinin M. Effects of monoamine oxidase inhibition by selegiline on concentrations of noradrenaline and monoamine metabolites in CSF of patients with Alzheimer’s disease.J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1993;5(3):193-202.

- Tariot PN, Cohen, RM, Sunderland, T, et al. L-Selegiline in Alzheimer’s disease: Preliminary evidence for behavioral change with monoamine oxidase B inhibition. Archives of GeneralPsychiatry 44: 427-33, May1987.

- Tariot PN, Sunderland T, Weingartner H, Murphy DL, Welkowitz JA, Thompson K, Cohen RM. Cognitive effects of Selegiline in Alzheimer’s disease.Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1987;91(4):489-95.

- Martini E, Pataky I, Szilágyi K, Venter V. Brief information on an early phase-II study with selegiline in demented patients.Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987 Nov;20(6):256-7.

- Martignoni E, Bono G, Blandini F, Sinforiani E, Merlo P, Nappi G.Monoamines and related metabolite levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with dementia of Alzheimer type. Influence of treatment with Selegiline. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1991;3(1):15-25.

- Goad DL, Davis CM, Liem P, Fuselier CC, McCormack JR and Olsen KM. Theuseof selegiline in Alzheimer’s patients with behavior problems. JClin Psychiatry52(8):342-5, August 1991.

- Schneider LS, Pollock VE, Zemansky MF, Gleason RP, Palmer R and Sloane RB. A pilot study of low-dose L-selegiline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol.1991 (USA)4(3):143-8.

- Falsaperla A, Monici Preti PA and Oliani C. Selegiline versus oxiracetam in patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. Clin Ther 12(5): 376-84, Sep-Oct1990.

- Monteverde A, Gnemmi P, Rossi F, Monteverde A and Finali GC. Selegiline in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer-type dementia. Clin Ther 12(4):315-22, Jul-Aug1990.

- Campi, N, Todeschini, GP, Scarzella, L (1990), ‘Selegiline versus L-acetylcarnitine in the treatment of Alzheimer-type dementia’, Clinical Therapeutics, 12:306-314.

- Schneider LS, Olin JT, Pawluczyk S. A double-blind crossover pilot study of selegiline (selegiline) combined with cholinesterase inhibitor in Alzheimer’s disease.Am J Psychiatry. 1993 Feb;150(2):321-3.

- Raffaele R, Rampello L, Veccio I, Giammona G, Malaguarnera M, Nicoletti G, Ruggieri M, and Nicoletti F. The use of selegiline in the treatment of cognitive deficits in elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. Suppl. 8 (2002) 319-326.